Tishman Center Contributes to Report to Address EJ & Urban Heat

Blog Post by Tishman Center Assistant Director Mike Harrington

Before we start, I want you to do a thought experiment. Think about the images you see on news coverage when there is a heat wave in a city (when it is about 95 F/ 35 C for a few days). What immediately comes to mind? Who do you picture?

For most of 2019 and the beginning of 2020, I was a part of the Urban Design Forum’s Forefront Fellowship, which is a program that brings together about 25 individuals with backgrounds in urban design, policy and development each year to discuss and offer solutions to pressing issues in large cities like NYC. The 2019-2020 topic centered on issues of environmental justice (EJ) in the city with two distinct team-based phases: Part 1 where we dove deep into the topic of extreme urban heat and Part 2 where we tackled individual topics that were of interest to us.

This post will focus mainly on the urban heat, which is no more timely than the other issues that I worked on which include zoning and housing, but especially during a time when more people should be indoors, or at least limiting time around other people due to COVID-19. It will be critical to have solutions for keeping people safe and healthy during heat waves, which are likely to increase due to global warming effects from the climate crisis, among other factors. To better understand why heat is so dangerous in cities and why it is an EJ issue we need to consider the urban heat island (UHI) effect and who it is affected the most by it.

The UHI effect (according to the EPA) is a phenomenon in places with more built environments, such as cities, which experience air temperatures that on average are about 1.8-5.4 F (1-3 C) degrees higher than rural areas surrounding them. This may not sound like a lot, but we are talking about the average temperatures, which don’t account for evening temperatures, which tend to be even higher than during the day. That is partially because the dark surfaces in cities slowly absorb heat throughout the day, which is released after sunset. There are many other factors that exacerbate this, including exhaust from air conditioning, density of people and other things, but basically cities are hotter than rural areas, especially areas where there is a lack of shade and vegetation.

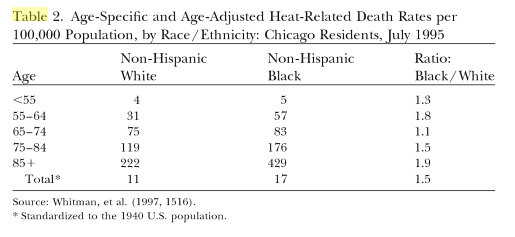

As for why this is an EJ issue, let’s look at the example of the 1995 heat wave in Chicago, where I am originally from. The sociologist Eric Klinenberg’s book Heat Wave, examined the disastrous two weeks in which nearly 800 people died from causes relating to extreme heat. To put that in perspective, an average about 600 people in the United States die from heat each year (with stats from 1999 - 2010), so for one city to have in excess of 700 in one summer shows that something really went wrong and is reminiscent of events like the 2003 heat wave in France. When Klinenberg took a look at who died during the heatwave, the majority of the deceased were elderly black people who lived in predominantly black communities. This stark comparison is revealed in Klinenberg’s chapters examining two adjacent neighborhoods; North and South Lawndale (also known as Little Village). The former being a predominantly black neighborhood that never recovered from harsh economic declines throughout the 70s and 80s and the latter a largely Latinx neighborhood with one the most thriving commercial corridors in the city.

North Lawndale, Chicago

In addition to this, the built environments and social characteristics of the neighborhoods are quite different. North Lawndale lost a lot of industry and physical buildings, leaving many vacant lots in the neighborhood with a lot of physical space in between people’s dwellings. The opposite is almost true in Little Village, where it can seem that there are always people out and about in close proximity to each other.

South Lawndale AKA Little Village, Chicago

While the two neighborhoods are literally right next to each other, North Lawndale had one of the highest death rates from heat in the 1995 disaster, while Little Village had one of the lowest. When he examined the community areas in the city, the majority of the deaths came from areas where black people lived. He and others that examined the heat wave found many other factors that contributed to the excess deaths, but it was clear that being black (and elderly) was an elevated risk for heat-related deaths. This is an unfortunate refrain we see with many other disparate impacts; We are seeing it with COVID-19 deaths, imprisonment, poverty, respiratory diseases, death from police violence, etc. All of these things are related and none of them are only affecting Chicagoans.

We saw similar patterns in NYC and other places when we were putting the report together and kept the EJ considerations in mind when preparing our solutions. The only way to combat systemic inequities is to address these problems systemically and that is why we provided the Mayor’s Office of Resiliency with so many recommendations. Be it from a design, policy or community actions, we wanted to provide a suite of solutions for policymakers in NYC and other major cities to implement in order to protect the most vulnerable from an issue that is only going to get worse with time due to global warming.

NYC Heat Vulnerability Map

One of the issues I worked on was that of perception in the media of heatwaves. I reached out to a reporter from Denmark, Sandra Brovall, and she enlightened me to the fact that most images we see during heat waves are of children playing, people exercising and groups having fun at the beach. What we don’t see are lonely seniors in stuffed apartments that either don’t have AC or cannot afford to use it. We don’t see the elderly men that have little social connections and therefore nobody to call on when they are being overwhelmed by constant high temperatures and would only need an hour of two of relief. Like many EJ issues, we choose not to look at the despair, pain and terror that injustice wreaks on our world. Some of the issues that we have, as a society, been able to change come from the images we see: the terror of dogs attacking protesters during the 1960s civil rights movement, the camera footage of Michael Brown and George Floyd that launched Black Lives Matter and the 2020 protests, respectively.

Some of the recommendations from the report

I hope that you find this report useful and timely and please feel free to read it here. I am thankful to the UDF, my great teammates and all of the others that helped us put this together. We don’t have to lose 600 people each year from this issue, and even if this report leads to saving a single life, it will be well worth the time and effort we put into it.